Since the 1910s, Korean architecture has shifted from traditional layouts to modern urban forms, sparking concerns over lost traditions and aspirations for global recognition. Those who grappled with these issues have become today’s leading architects, blending tradition and modernity to forge a distinct identity for Korean architecture and earning worldwide acclaim.

1910년대 이후 근대적 도시 구조를 급격히 받아들인 한국 건축계에는 단절된 전통에 대한 고민과 한국 건축의 세계화에 대한 열망이 존재했다. 오늘날 주목받는 한국 건축가들은 전통·근대·현대를 융합해 한국 건축의 고유성과 자신만의 언어를 확보하여 세계에 한국의 이름을 알리고 있다.

Writer. Jinyoung Lim

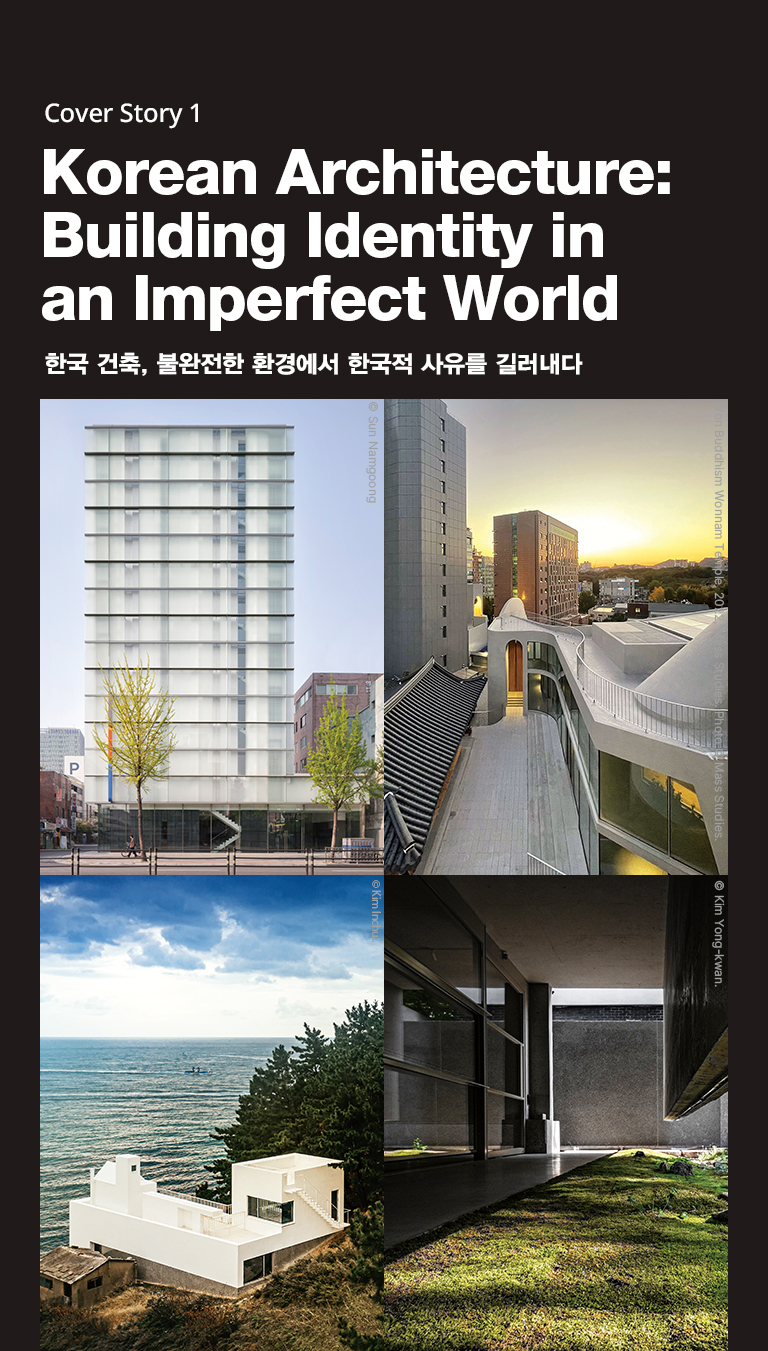

“Kpop Demon Hunters” art director Celine DaHyeu Kim established the following principles when depicting Seoul in the work: Avoid excessive clusters of skyscrapers as they give off a New York vibe. Avoid messy mixtures of different-sized buildings without mountains or hills, as this feels like Tokyo. Clear differences in scale create wonderful contrasts, so let nature unfold between high buildings arranged like walls and small buildings spread like blankets. This accurately shows the characteristics of Korean cities.

Korea’s traditional urban structure adapts to the natural environment. However, following liberation from Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953), rapid modernization and industrialization dismantled existing urban structures. In cities that underwent rapid development, traditional, modern and contemporary periods existed alongside each other in a fragmented manner. Consequently, unregulated and undefined spaces appeared in various locations, exhibiting characteristics not typically observed in planned urban environments.

Following changes in tradition, the Korean architectural community considered the question of how to define the identity of Korean architecture. Furthermore, given that modern architecture was embraced at a comparatively later stage, they undertook the challenge of determining how to establish their standing within the global architectural community. Korean architecture today is shaped by architects who have faced these challenges firsthand. After 1989, when Korean citizens gained the ability to travel internationally, architects studying abroad began to consider the defining characteristics of Korean architecture.

They sought answers while adapting to Korea’s reality of building fast and cheap in a world where things often disappeared rapidly. What had once seemed like a weakness in Korean architecture eventually became, through years of exploration, its greatest strength. Korean ideas expressed through modernist principles took many different forms and approaches. Like shattered glass that catches light more brilliantly than whole panes, Korean architecture began weaving together scattered urban green spaces, working with natural topography and connecting labyrinthine neighborhoods to create landscapes that were unmistakably Korean. What emerged was an authentic character that was beautiful precisely because it wasn’t perfect.

This distinctive evolution of Korean architecture is clearly evident in the work of several key architects. The projects of Cho Byoung Soo, Cho Minsuk, Choi Wook and Kim Chanjoong are perfect examples. Each demonstrates a unique identity and universal appeal in their own way, together defining what Korean architecture looks like today.

The archetype of Cho Byoung Soo’s architecture lies in the Concrete Box House and Earth House. From the outside, it’s a simple concrete box, but once you step inside, you will find that the same-sized patch of sky opens above a water feature. Light falls into the courtyard while the ever-changing sky brings wind. Inside, reclaimed traditional Korean house materials are arranged organically, creating structural experiments that directly connect concrete and wood while evoking familiar emotions.

Jedong Ranch: Meditation Space, 2010 / © Hwang Wooseop.

Jedong Ranch: Meditation Space, 2010 / © Hwang Wooseop. Namhae Southcape Linear Suite and Villas, 2013 / © Hwang Wooseop.

Namhae Southcape Linear Suite and Villas, 2013 / © Hwang Wooseop.

Earth House is even bolder. The box carved into the earth becomes a courtyard, with a house shaped like a straight line featuring three rooms and a wooden platform tucked to one side. Descending narrow hillside stairs to reach the courtyard, the earth’s boundaries frame a square of sky. Here, Cho Byoung Soo designed not a building, but the land itself.

In the late 1980s, while in the United States, Cho Byoung Soo encountered doubts and critiques of contemporary architecture. He felt the need for “experiential architecture” beyond visual proportions and forms—“humanistic architecture” that communicates with nature. He believed Korean architecture could provide this alternative. He sought to find the abstraction and organic qualities that modernism had lost in nature-friendly Korean architecture, hoping to complement contemporary architecture through a warm sensibility.

Working with tight budgets, Cho Byoung Soo actively embraced the materials and construction methods available within Korea’s industrial system. He also experimented with restrained forms. In the Concrete Box House, he attempted self-waterproofing by enhancing concrete surface tension without traditional waterproofing. He eliminated the protruding structures at roof edges that typically block rain and wind, creating a smooth 20-centimeter-thick roof.

Cho Byoung Soo describes the practicality and improvisational aesthetics permeating Korean spaces as mak—a Korean sensibility discovered in the beauty of rough pottery bowls shaped quickly and simply. His architecture presents the aesthetics of mak: the beauty of unpredictability rather than perfectly orchestrated order. “I think it’s time to focus on the comfort and humor that emerge from adapting to nature and the aesthetic qualities that arise from this.” This approach also captures contemporary regionality in Korea, where traditional architectural methods and industrial foundations have been disrupted.

Namhae Southcape Linear Suite and Villas, 2013 / © Kim Yong-kwan.

Namhae Southcape Linear Suite and Villas, 2013 / © Kim Yong-kwan.

Choi Wook integrates buildings from different periods and styles and creates continuity in spaces with multiple structures. Gahoe-dong Duzip (The House of Sulhwasoo Bukchon) involved renovating and connecting a 1930s Hanok (traditional Korean house) with a 1960s Western-style building. To seamlessly connect these different architectural styles, he removed the retaining walls between the buildings and created a basement level in the Western-style house that connects to the Hanok’s courtyard. Choi made Hanok walls from glass and created diagonal land flow between the buildings, so visitors experience spatial transitions.

The Room of Quiet Contemplation at the National Museum of Korea houses two national treasure gilt-bronze pensive bodhisattva statues. Choi wanted to present a synesthetic experience transcending time and space, moving beyond Western visual perspective. In the deep, stage-like space where visitors can read the bodhisattvas’ expressions, he finished the walls with light-absorbing earth and charcoal. By eliminating a central focal point, he encourages subtle visitor movement. This approach demonstrates attempts to materialize Korean architecture’s spatial sensibilities—contrasting with Western geometric logic—through meticulous planning and precise measurements.

The lobbies of major buildings like the Hyundai Card headquarters and 1964 Building don’t focus attention on a single point but scatter it in multiple directions, encouraging people to survey the space broadly. By carefully modulating the ground plane, Choi creates sensations that connect to the city. Rather than emphasizing façades, he reveals structural elements or uses opaque materials to soften exterior impressions.

While studying at Venice University, surrounded by progressive theorists and architects, Choi realized that Eastern and Western thinking and philosophy are fundamentally different. From the contrast between Western music that builds harmony by layering notes and traditional music where five notes race forward, he discovered that Korea represents a “world of juxtaposition.” Instead of pursuing visual formal aesthetics, he chose to explore and implement Korean spatial principles.

“I try to understand the land and surrounding conditions. I work to create continuous cross-sectional sequences—the relationship between the building site and its surroundings.” Choi transforms the synesthetic qualities embedded in Korean architecture, the “atmosphere” that might otherwise remain vague, into concrete measurements and precise construction methods, elevating it to a spatial experience.

GENESIS Cheongju, 2025 / © Kim Inchul.

GENESIS Cheongju, 2025 / © Kim Inchul. Gahoe-dong Duzip (The House of Sulhwasoo Bukchon), 2022 / © Kim Inchul.

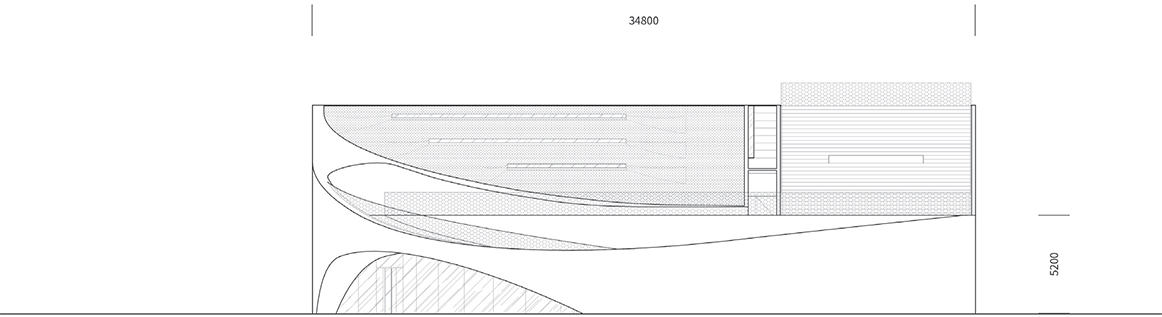

Gahoe-dong Duzip (The House of Sulhwasoo Bukchon), 2022 / © Kim Inchul. Space K Seoul, South Elevation, 2020, Mass Studies. Drawing © Mass Studies.

Space K Seoul, South Elevation, 2020, Mass Studies. Drawing © Mass Studies.

The Serpentine Pavilion, which has featured the work of outstanding architects for 25 years, selected Cho Minsuk last year. To design the pavilion, he traced the history of previous pavilions, then emptied the most-used central area and spread five pavilions like islands. The title: “Archipelagic Void.” Like Korean pavilions that create voids while framing surrounding landscapes, spaces with different functions—gallery, auditorium, library, play tower, tea house—engage their surroundings while creating interstitial spaces. Cho compares this to “Korea’s dining table.” Unlike Western meals served in sequence, Korean tables present multiple dishes simultaneously, creating numerous possibilities with everything happening at once. It becomes a “collective experience” where people gather for different purposes—listening to music, reading, drinking tea, physical play, etc. Traditional materials like wood and limestone foundation stones coexist naturally with industrial materials like mesh and polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Cho explores Korean cities from an observer’s perspective. His early projects created fissures in uniformity by shifting or voiding floors in standardized high-rise developments. From the Kakao headquarters that expands space through concrete shell modules to Space K Seoul Museum of Art (Space K Seoul), which uses flowing curves to create urban movement, to Won Buddhism Wonnam Temple, his work shows flexibility and diversity in structural approaches. While Space K Seoul introduced a new flow to a characterless new town block through curves, the curves of Won Buddhism Wonnam Temple connect an isolated, single-access site to seven different neighborhood streets.

Rather than creating urban icons, Cho intervenes as an observer and mediator. Through an exhibition exploring how modernity was absorbed along different trajectories during Korea’s division in 2014, he became the first Korean to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Cho believes architecture is a “device that catalyzes social relationships.” “Even with a hundred people, you need to create the feeling of being in a living room. What architects can do is design spaces that feel genuinely welcoming and generous, where anyone can feel they belong.”

Serpentine Pavilion 2024, Archipelagic Void, designed by Minsuk Cho, Mass Studies.

Serpentine Pavilion 2024, Archipelagic Void, designed by Minsuk Cho, Mass Studies.  Space K Seoul, 2020, Mass Studies. Photo © Kyungsub Shin.

Space K Seoul, 2020, Mass Studies. Photo © Kyungsub Shin.

Kim Chanjoong’s first Korean project involved renovating numerous pedestrian tunnels with short design and construction schedules and minimal budgets to improve people’s access to the Hangang River. He solved the problem using polycarbonate modules—industrial materials offering transparency, impact resistance, heat resistance and workability—perfect for a Korean market demanding things “cheap and fast.”

“Look a little deeper and you’ll discover that forms contain optimized systems for spatial composition, structure, budget and fabrication.” Within architecture’s massive industrial framework, he approached buildings as industrial systems of components and prefabricated elements to respond to market demands.

He also experimented with industrial materials like fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP), eventually working with Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC), a civil engineering material, for irregular concrete modules. Traditional formwork is removed once concrete hardens, but he designed formwork to remain as building elements like insulation. KEB Hana Bank PLACE 1 SEOUL and Ulleungdo Island’s KOSMOS resort demonstrate UHPC as architectural cladding, presenting his concept of “industrial craftsmanship” to the public.

Organic forms aren’t actually Kim’s goal. Rather, the process of creating irregular modules for efficient structural stability was key. Interestingly, international audiences view Kim’s work, which is focused on problem solving, as distinctly Korean—precisely because it emerges from responding closely to Korean conditions.

These architectural techniques recently appeared in Gentle Monster’s Seoul headquarters “HAUS NOWHERE SEOUL.” Using UHPC, he fulfilled the client’s request for a “strange but beautiful” building by boldly composing three functions: retail, office, and upper-level voids.

Kim brings industrial materials and fabrication methods into architecture, responding to Korea’s rapidly changing market while pursuing new architectural possibilities. Through ongoing intervention in manufacturing processes and continued experimentation, his work expands from components to systems to convergence.

Mercure Ambassador Seoul Hongdae, 2020 / © Kim Yong-kwan.

Mercure Ambassador Seoul Hongdae, 2020 / © Kim Yong-kwan. HAUS NOWHERE SEOUL, 2025 / © Kim Yong-kwan.

HAUS NOWHERE SEOUL, 2025 / © Kim Yong-kwan.